Since the early days of this blog, many entries have been focused on anger — or angrief as I like to call it.

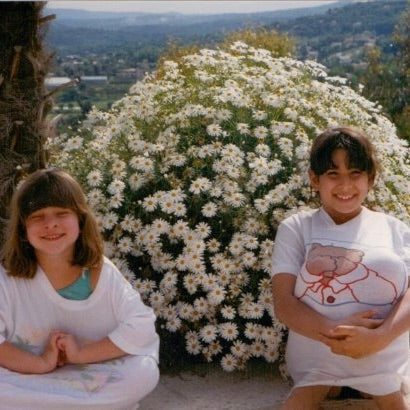

I had no shortage of angrief. My anger was less so focused on my family’s circumstances (my dad died after a long illness when he was 54 and my sister died unexpectedly when she was 37) and instead directed towards the people around me. Resentment at my friend’s insensitive husband. Rage at my absent coworker. Loathing for the random person I heard complaining about their latte foam.

My sister has now been dead for nearly 2,000 days. So much time that I no longer imagine her at every family gathering. Somewhere between days 957 and 1,230, it stopped being uncomfortable to have her missing from a family photo. I never accidentally pick up my phone to text her (but she’s obviously still in the Favorites folder of my contacts and likely always will be).

In the early days of her absence, I imagined that I would never get used to this reality. But, here I am, and I feel sorta-kinda used to having a dead sister. It’s still unpleasant and a reality I’d never ask for, but it doesn’t surprise me as much as it used to. And the anger that once consumed nearly every minute of every day is so much softer.

I can understanding the intensity of the feelings I once had, but instead of feeling them in the present I think, “Oh, if this friend had spent 10 minutes complaining about their ungrateful younger sister 3 years ago, my knees would have been shaky and I would’ve felt like I were going to pass out.”

Grief stages are bullshit, but I think you might be able to loosely connect your grief to a the progression of a human life.

For me, the early days were similar to the 4th trimester. I couldn’t see more than 12 inches from my face, most times I just wanted white noise, a tight swaddle, and someone to magically get rid of my constant crying-induced congestion. A NoseFrida for adults would have been really helpful.

The toddlerhood stage was defined by reactivity. The time I shrieked and fell to the floor when I couldn’t decide on what to make for lunch. There was the week I seethed and cried for days about my building’s plan for pest control. I was entirely focused on myself, and those poor mice my building wanted to poison. No one else’s opinions or experience mattered. I wasn’t mentally capable of looking at a situation from another person’s point of view.

My current stage of grief is maybe the equivalent of an 18 year-old. Still relatively fresh-faced, and having an underlying (and incorrect) assumption that I have it mostly worked out.

In the absence of anger…understanding?

In this mostly anger-absent state, I feel compelled to offer a bit of praise to the grief adjacent — those very same people I complained about so many times before.

No longer suffering under my tragedy haze, I can see that they were trying their best, or maybe even not really trying at all. And while I previously held hatred for both of the aforemention parties, I no longer do. Even for the folks who didn’t try.

Now that I feel like I’ve somewhat returned to my baseline, friends and family are now going through their own shit (I mean, they always were, but now I have the capacity to notice and empathize).

I can relate to being a member of the grief adjacent which I now see both sides of the coin more clearly. Sometimes I show up and do so pretty well, sometimes I say the wrong thing, and sometimes I don’t do anything when I should have or because I don’t have the capacity to do so.

Loving the bereaved is a task that requires patience and confidence in the face of uncertainty. The bereaved may be volatile in nature. They will likely abandon social norms. Do not expect a thank you card or text. Do not expect them to remember your birthday for the next few years. They will not move through grief like how you move through grief. You will be at a loss on how to support them. You won’t know if they appreciate what you’re doing. Loving the bereaved means being in it for the long haul with very little feedback.

To the friends and family who love someone who is hurting. You are seen. Your job is not easy, there is no guide book, and the rules constantly change. We all tend to like relationships with predictability. You give a little, they give a little. But your relationship right now may require you to give a lot and receive very little or nothing in return.

Relationships that survive life’s biggest losses tend to be our most meaningful connections. One of my greatest sources of gratitude is for the people who were brave enough to show up for me when I offered very little feedback in return.

If you feel at a loss about what to do to support a friend or relative who is hurting, start small. Here are a few ideas:

- Check in regularly with no expectation that you’ll hear back (a simple ‘thinking of you — no need to reply’’ text works well)

-

Drop off snacks or a meal.

-

Offer to help with a chore — dog walking, grocery shopping, take the children for the afternoon.

- Don’t pretend it’s not happening. Sometimes we feel compelled to bring the cheer and ‘good vibes’. Acknowledging someone’s pain doesn’t remind them that they’re sad. It lets them know that they’re seen and that what they’re experiencing is very real.

_____

Here For You offers fully customizable care packages for family and friends living through life's toughest transitions. Our practical gifts range from curated household essentials to customizable sets of self-care items, all prepared with a personal touch.

2 comments

When the man I was going to marry passed away people offered to help me with some repairs on my house. However, they did not understand that I just could not take anyone being in the house right after the died they just driffed away. I never got any help. And they all stopped coming by unless it was something they wanted my best friend over sleep that Morring of the services and I was all alone it still hurts and it been 12 years.

Thank you for your honest postings. When it’s difficult to find someone to turn to who may understand partly what I’m thinking, I found your blog. It’s nice to see that someone has had similar thoughts or emotions on this grief journey!